BY LETTER

Orwoods (Dyson Trees)

Technology > Technology Type or Material > Gengineering

Technology > Technology Levels > High Tech / Hitech

Technology > Application > Infrastructure

Technology > Technology Type or Material > Organic/Biotech

Technology > Technology Levels > High Tech / Hitech

Technology > Application > Infrastructure

Technology > Technology Type or Material > Organic/Biotech

Genetically modified or artificially-created trees and forests that thrive in freefall | |

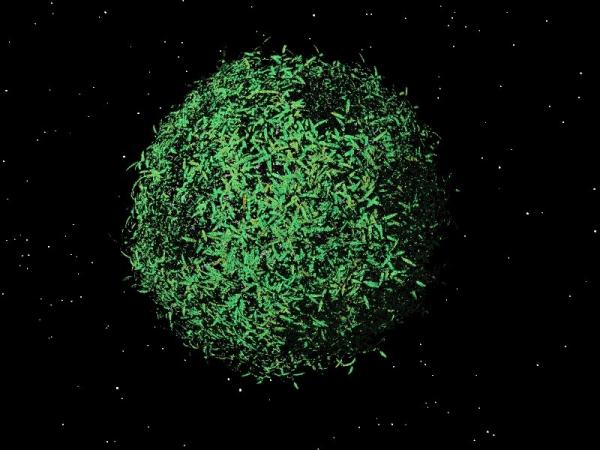

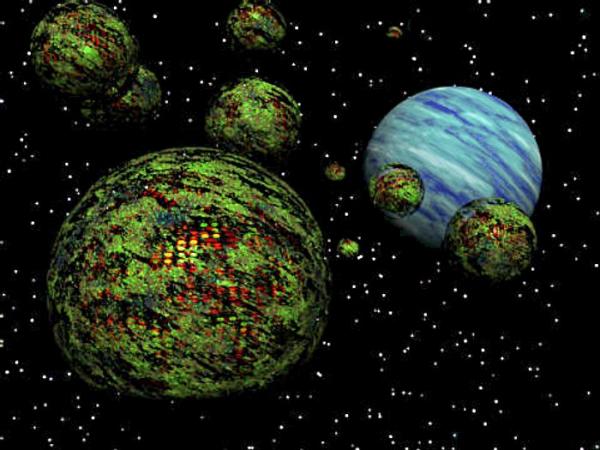

Image from Anders Sandberg | |

| The Dyson Tree at Jambori, Nuicrick Plexus, Zoeific Biopolity. This relatively young tree is as yet sparsely populated, and does not show the massive hab development, utility fog wisps, and shuttle traffic characteristic of the more densely inhabited trees. | |

An Orwood ecology constitutes a stable or evolutionary space-based biota, with or without symbiotic sentient (human, neogen, etc.) interaction. The individual organisms in such an ecosystem may live wholly within the tissues of the trees concerned, or be capable of thriving in vacuum and travelling between the trees through space.

Many Dyson trees contain spaces within their tissues which can support life; these spaces are often configured into comfortable habitats for modosophonts, complete with breathable air and access to water. To further support life, these trees produce edible fruit and other consumable products within the habitable spaces; in an Orwood, these habitable spaces may be large and support not just modosophonts but an entire ecology which has a complex symbiotic relationship with the tree's life cycle.

Organisms which can travel through space between different Dyson Trees may carry genetic material or other useful data, or may translocate physical resources that can help the tree to grow, reproduce and to better interact with local environments and cultures.

Biology

A fully grown tree is a spherical structure up to a hundred kilometers across. It generally consists of 4-6 trunk structures growing out from a comet nucleus. Branches grow from the top of each trunk and intertwine and merge with each other to form a single structure. The trunks and primary branches are hollow and contain a breathable atmosphere and symbiotic ecology as well as a space adapted ecology on their exteriors. Various sub-species have been engineered to survive at a variety of distances from a star and under various wavelengths. Generally found at distances ranging from 0.5-4 AU around stars in the G K and M class. Often a popular habitat for space adapted bionts.Growth of a new tree begins when a suitable comet is diverted into a close solar orbit and a seed is planted on it. Over several years the seed extends a root system into and around the comet and then begins the growth of the primary trunk systems. Depending on the material supply in the comet and the distance from the star, full growth may take up to a century. However, most trees are ready for initial habitation within 10 years of planting. Average tree lifetimes run to a millennium even without life-extension bio-nano, and a mature tree may support a population in the millions.

In systems where Dyson trees are long-established, entire 'orbital forests', consisting of hundreds of trees spread across millions of cubic kilometers, may be found in the most desirable orbits.

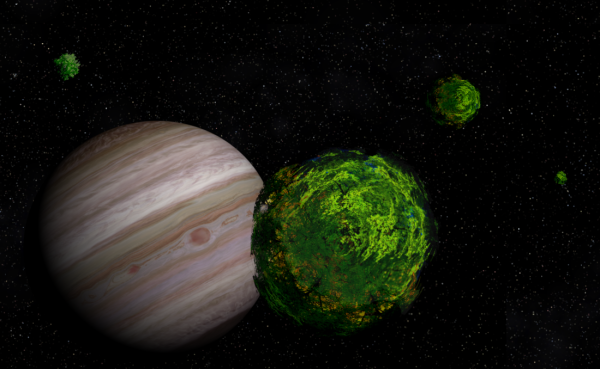

Image from Steve Bowers | |

| Orwoods orbiting the gas giant Massey-Bromlei are close enough to share elements of their symbiotic ecology. | |

History

The first experimental dyson trees date from as early as the Middle Interplanetary period. Unfortunately, none of the early trees survived the Technocalypse.The idea was however popular enough to be taken up again by the First Federation, with diverted a number of comet cores from the Oort Belt. Unfortunately, many of these cores had already been long populated by haloist clades, and most either wouldn't give up their cores, or did so only after exorbitant financial remuneration. A typical cartoon from the period showed a crusty, skinny old microgravity-adapted space prospector sitting on a lump of ice, frowning, head turned away, arms and legs (prehensile feet) crossed, while slickly dressed developers in the latest Xoffona-6 suits wave wads of Fedcred in eir face.

Tree-based development projects only really took off during the Age of Expansion, supported by clades of spacers and biotech megacorps.

These days dyson trees are very popular in the Zoeific Biopolity, the Utopia Sphere, MPA, the Negentropy Alliance, and the Sophic League. And since the seeds are relatively cheap compared to most technological solutions, and more reliable than a lot of nano, growing dyson trees has also become a common way of building a base in the Outer Volumes.

There are even wild versions of dyson trees. These propagate by sending seeds that are propelled by solar sails, chemical rockets, or even amat-propelled devices. Whole ecologies have spring up in some star systems.

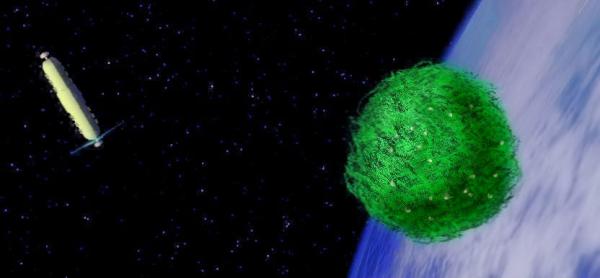

Image from Steve Bowers | |

| Two High Cycler habitats at closest approach to Corona; a closed cylinder habitat and a 25 km orwood tree | |

Habitats

While many trees away from the Nexus in the Inner Sphere and Middle Regions, and especially the Outer Volumes, are only lightly populated, many trees in Nexus linked Inner Sphere systems are heavily populated, with a dense swarm of shuttles, ships, and other vehicles weaving among breaks in the foliage, along with docking stations, control towers, manufacturing faculties, clusters of space homes, water-filled diamondoid spheres glowing in the dark like blue pearls, others green like lush forests - little forests within a larger dyson forest - computronium banks, etc etc.Some dyson forests have their own hyperturings and caretaker gods looking after them, and these generally restrict the population to a small number of carefully-screened individuals who will respect the forests. Other Orwoods are simply comfortable and safe places to live, whether or not they have transapient oversight.

But a number of Orwoods have been deliberately designed to be tourist attractions and entertainment complexes. The (in)famous Makrania Orwoods around Frei (HJer-IV, NoCoZo) are well-known across the Terragen Sphere for their zero gravity free-space casinos, sports and hedonics.

Image from Todd Drashner | |

| The Macrania Orwoods around Frei | |

There are many other Orwood variants, including cyborg and bioborg trees: synanotech trees which are half organic and half artificial: trees that incorporate utility fog environments that can simulate almost any environment, and innumerable other combinations. Increasingly common are xenobiont trees that are adapted from alien tree-like species, and which may be inhabited by xenosophonts of various kinds or by terragens with suitable adaptations.

Snowglobe Trees | |

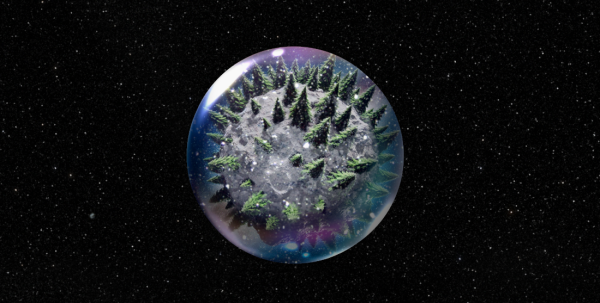

Image from Steve Bowers and DreamUp image creator | |

| A Snowglobe Tree in the outer Tau Ceti system | |

Oortwoods | |

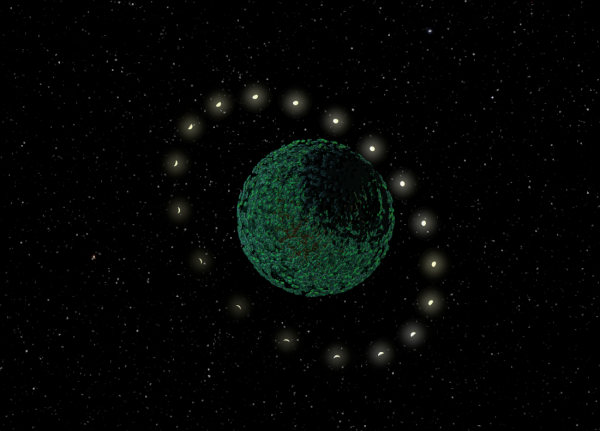

Image from Steve Bowers | |

| An Oortwood in deepspace illuminated by a ring of small fusion-powered Artisuns | |

These habitats are remarkably diverse. The source of illumination may come from small artisuns which are arranged externally to the foilage, or from a hotpoint located deep within the structure. Although many share much of their physiology with typical orwoods, others utilise unconventional forms of photosynthesis in order to exploit a wider range of energy sources, and may resemble lichen, fungus or even animal tissue.

While some Oortwoods have been constructed by Hiders, others are made either for a general desire for isolation or as art projects as these organic structures are generally bad at hiding heat. These structures are popular among the Deeper Covenant.

Rotating Orwoods | |

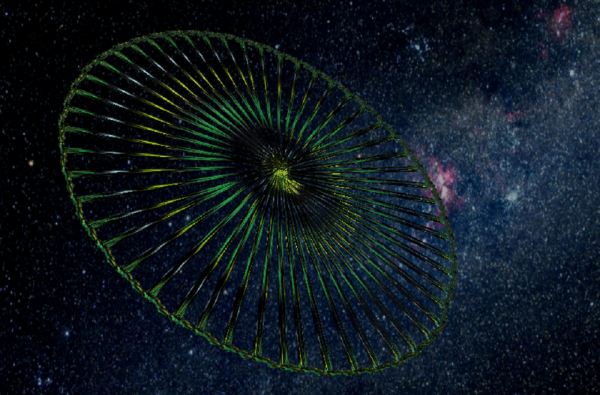

Image from Steve Bowers | |

| Sacredtree is a large Orwood which rotates to give a range of different values of centrifugal gravity at different distances from the hub | |

Yggdrasil Bushes, Greenbubbles and Canopy Plants

Other biologically-constructed habitat concepts which share many features in common with Orwoods include Yggdrasil Bushes, Greenbubbles and Canopy Plants, various kinds of habitat which incorporate large internal spaces covered by organically grown worldhouse roofs.Examples of different Orwood variants

The following are only a few of the many worlds and star systems that include extensive Orwoods:- Deepwood - Deep space orwood species of probable alien origin.

- Ecotopia Dyson - includes numerous clusters of orwood forests.

- Makrania Orwoods - NoCoZo hedonics system.

- Parvati Orwood - home and origin of the Astomi.

- Phytotopia - embedded transapient orwood intelligences in the Gyanti System, affiliated with the Utopia Sphere.

- Sacredtree - Orwood Forest and system in the Zoeific Biopolity.

- The Underwoods - Orwood complex and Belts at Ao Lai (Gamma Leporis B).

Related Articles

Appears in Topics

Development Notes

Text by Todd Drashner, M. Alan Kazlev

Oortwood material by keeperofbeesandtruth, Snowglobe material by Andrew P, Additional material by Steve Bowers and Robin Denley Bowers

Initially published on 17 December 2001.

Oortwood material by keeperofbeesandtruth, Snowglobe material by Andrew P, Additional material by Steve Bowers and Robin Denley Bowers

Initially published on 17 December 2001.